Making African Connections: Uncovering the Role of Soba Tchiliwandele

Dr. Nicola Stylianou is the Post-Doctoral Research Associate on the ‘Making African Connections’ project. In this blog she writes about how the project is recovering the narratives of Africans whose assistance helped the Powell-Cottons to make their collections, and the Museum.

‘Making African Connections: decolonial futures for colonial collections’ is a two-year project funded by the AHRC and run by the University of Sussex. The project focuses on three collections of African objects which are currently held in museums in Sussex and Kent. Preliminary research, done while devising the current project, revealed that the museums of Kent and Sussex had a wealth of material from Africa that was bought to the UK during the colonial period. We decided to focus on three museums which had very strong collections which were, in some way, historically significant.

We were delighted when the Powell-Cotton Museum agreed to be one of our partners as their collection of African artefacts is outstanding and deserves to be brought to a wider audience. We are focusing on the trips to Angola made by Diana and Antoinette (Tony) in 1936 and 1937. Each trip lasted several months, and they bought back thousands of objects. Approximately 2,500 objects remain in the collections of the Powell-Cotton Museum while a slightly smaller number were sent to other museums in the UK and Europe. It is an extremely large collection even by the standards of the Powell-Cotton family! The collection includes dolls, jewellery, clothing, domestic items, weapons, medical equipment and samples of plants.

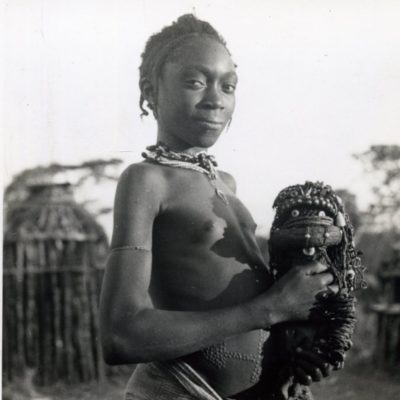

Young girl holding a doll similar to those collected by the Powell-Cotton sisters.

We were delighted when the Powell-Cotton Museum agreed to be one of our partners as their collection of African artefacts is outstanding and deserves to be brought to a wider audience. We are focussing on the trips to Angola made by Diana and Antoinette (Tony) in 1936 and 1937. Each trip lasted several months, and they bought back thousands of objects. Approximately 2,500 objects remain in the collections of the Powell-Cotton Museum while a slightly smaller number were sent to other museums in the UK and Europe. It is an extremely large collection even by the standards of the Powell-Cotton family! The collection includes dolls, jewellery, clothing, domestic items, weapons, medical equipment and samples of plants.

The sisters listed everything they bought detailing what they paid, what it was called in the local language, where they bought it and, sometimes, the name of the person they bought it from. There are also thousands of photographs, several hours of films, diaries by both sisters, sketches, rubbings and detailed ethnographic notes on a wide variety of topics. This additional material makes the collection extremely important because it allows us to understand a great deal about the context in which the collection was made and to identify the Angolan people who created the collection with the sisters. I am working with Dr Inbal Livne, Head of Collections and Engagement at the Museum to introduce the results of some of this research into the gallery.

Diana Powell-Cotton packing some of the objects collected during their 1937 trip to Angola.

One of the people who worked with the sisters to create the collection was Soba Tchiliwandele. A Soba is a term still used in Angola and denotes the chief or headman of a village. It is the most local form of authority and directly above it is the Chefe de Posto. Tchiliwandele hosted the sisters from 30 May to 2 June 1937. There are approximately sixty objects currently in the collection which we know are associated with him in some way. We also know that objects associated with him can be found in the British Museum and the Marischal collection, Aberdeen.

Diana and Antoinette relied on a network of Soba’s and other local leaders to provide access to people, to collect objects and to allow them to move freely in rural Angola. The previous year the sisters had stayed with a man called Kanguli who was Tchiliwandele’s half-brother and it seems that it is through Kanguli that the arrangement to spend some time with Tchiliwandele was made. Tony notes in her diary that Tchiliwandele had been well prepared by Kanguli and knew what the sister’s wanted before they arrived.

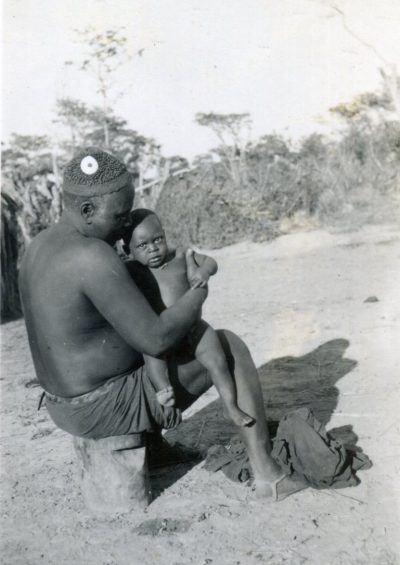

Soba Tchiliwandele holding a small child. He sold his hat to the Powell-Cottons but not the conus shell adorning it. The Powell-Cottons had to find an alternative conus for their collection.

During the 1930s Sobas were losing some of the powers they had traditionally held to the Chefe de Posto as the Portuguese colonisers sought to concentrate power in fewer individuals. Diana’s diary records that Tchiliwandele said he no longer had certain rights that he used to have, for example it used to be up to him to decide whether somebody from elsewhere could settle in the area but now that decision rested with the Chefe de Posto. Tchiliwandele also tells an anecdote that shows how serious disputes between the Chefe and the Soba can be. Tchiliwandele’s uncle Tchipwapwa had been Soba before him and while he was Soba he travelled to Benguela (a city on the coast) where he was presented with a folding chair and blanket by a Portuguese government official. When he returned the Chefe de Posto in his area did not believe these things had been presented to him and shot him. As a direct result of this Tchiliwandele became Soba but also had to move his homestead and his people to another area.

Tony describes Tchiliwandele in her diary as ‘Very fat, oldish man but energetic and seems dignified and sympathetic. Wore String cap with conus shell at each side, worn by all sobas, made here. The conus shells belonged to his uncle the former chief.’ Later she records that ‘Soba Tchiwandele sold club, walking stick, wristlet and string cap of his uncle, a former chief’. We have identified this cap within the collection but it was sold without its conus shell, suggesting that while Tchiliwandele was willing to part with the cap he kept the shells as they were valuable and a sign of the position he and his uncle held. The sisters bought a different shell later during the trip which was attached to the hat.

A small exhibition currently on display at the Powell-Cotton Museum tells the story of Tchiliwandele and includes a display of objects he owned and those he helped the sisters acquire.

More information about the ‘Making African Connections’ digital archive project can be found here.