The Kashmir Diorama

Fenja Schultz is a student at the University of Kent, studying for a BSc in Biological Anthropology. She is currently undertaking a year of professional practice at the Powell-Cotton Museum, examining the history of the Museum’s oldest diorama. Here she tells us about what she’s uncovered so far:

Before his extensive trips all across the African continent, Percy Powell-Cotton spent several years travelling across the Indian subcontinent, with a special preference for hunting trips to Kashmir and west Tibet. Having first been to Kashmir on his World Trip (March to October 1890), he returned three more times, in 1892/93, 1894/95 and 1897/98, the last trip lasting a whole 15 months. Some of the animals he collected on these four trips can still be seen in the museum, being skilfully prepared by Rowland Ward’s Ltd and mounted in the impressive Kashmir Diorama.

Just as the Kashmir trips were among Percy’s earliest travels, the resulting diorama is the oldest in the Museum and potentially one of the oldest remaining large sized dioramas in the world. However, despite its age, relatively little is generally known about its history and development. Luckily, even at this early stage in his career, Percy Powell-Cotton was a very thorough note taker, and most of his notes, diaries, photographs and letters are preserved in the Museum’s archive. Working through these materials has revealed a lot of information.

One of Percy Powell-Cotton’s maps. These are annotated with very small and hard to read details.

Construction of the diorama (and the Museum as a whole) began in 1896/97. In June 1897 the structure of the pavilion intended to house Percy’s ever-growing collection was completed, and by September, the first lot of skins and skulls was sent to Rowland Ward Ltd to be taxidermied and later set up for display. The construction of the diorama continued for over 10 years, with animals being added on at least three different occasions. In August 1909 the artist T. Bryant Brown was hired to paint the splendid background of the case, displaying a view on the Baltoro glacier (close to the town of Gilgit). Brown later also worked on the first African case (now in gallery 3) and helped with the foreground scenery such as rock work. Until spring 1910, Percy struggled with setting up the walnut tree, now an impressive centre piece of the diorama. The leaves on the tree were handmade by Percy and his wife Hannah, and way more than expected were required. In June 1910 the case was almost ready to be sealed up, with only a small number of mounts still missing.

Taxidermied animal specimens waiting to be fitted into the Kashmir diorama.

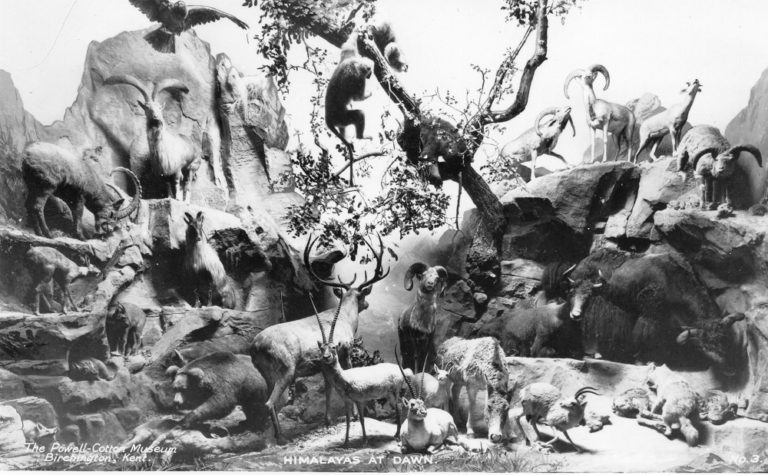

Nowadays, the diorama houses 42 animals from modern day Jammu and Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan and Tibet. The majority of the mounts (19 of 42) were made from specimens collected on the last trip to Kashmir. It included a detour into Tibet to hunt yak, and Percy even wrote a little adventure story about it. As Percy first travelled in Kashmir during his World Trip, when he was still mainly focused on collecting trophies, no complete specimens from this trip can be found in the diorama. However, one of the Tibetan Antelopes (Chiru) was mounted with a skull collected on the first trip. This is something that was quite commonly done, as Percy wanted to display only the best and most impressive of animals, so if horns were broken off or in a bad condition, a more impressive skull would be used. Percy had very concrete ideas on how he wanted each animal to look, so when he sent them to the taxidermist, he not only provided instructions on the general position they were to be mounted in, but also on the story he wanted to tell. Examples are the markhor which has been driven over the cliff by wolves or the serow which is about to charge at a threat.

Since its completion in 1910, the diorama has remained essentially unchanged. In summer 1919 pests (mainly moths) were discovered in the case, however with the help of Rowland Ward Ltd (Mr Ward himself had already died), his own knowledge of preserving specimens and a selection of strong chemicals, Percy managed to save his specimens. All animals seen in the case have been displayed there since at least 1920.

Despite all this information having been uncovered and brought together, may open questions about the diorama still remain, including some mysteries about some of the animals, and will hopefully be resolved in the next phase of research.

The Kashmir Diorama on completion.

The Kashmir Diorama on completion.

The Kashmir Diorama as it looks today.